Pericolosità Naturali

Maremoti

Preparato da CERG – European Centre on Geomorphological Hazards – Strasbourg, France & the Editorial Board

Lo Tsunami (parola giapponese che significa “onda del porto”), o “maremoto” in lingua italiana, una delle forze della natura più terrificanti, consiste in una serie di onde oceaniche di grande lunghezza d’onda e di lungo periodo, generate in un determinato volume d’acqua da una perturbazione impulsiva che ne determina lo spostamento.

Lo tsunami è composto da 5-6 onde di cui la prima è di dimensioni minori e viene chiamata “onda gentile”. La seconda e la terza onda rappresentano le onde più alte e maggiormente distruttive.

Lo Tsunami (parola giapponese che significa “onda del porto”), o “maremoto” in lingua italiana, una delle forze della natura più terrificanti, consiste in una serie di onde oceaniche di grande lunghezza d’onda e di lungo periodo, generate in un determinato volume d’acqua da una perturbazione impulsiva che ne determina lo spostamento. Il maremoto è composto da 5-6 onde di cui la prima è di dimensioni minori e viene chiamata “onda gentile”. La seconda e la terza onda rappresentano le onde più alte e maggiormente distruttive.

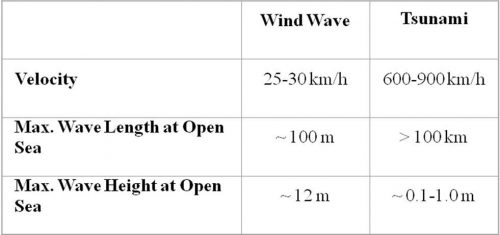

In mare, le onde di maremoto hanno un’altezza inferiore a 60 cm – non identificabili né da navi, né da aerei. Al contrario, la loro lunghezza è spesso superiore a 160 km, molto superiore rispetto alla profondità del fondale marino su cui si muovono. Un confronto tra le caratteristiche delle onde generate dal vento e quelle delle onde di maremoto è riportato in Tabella 1. Quando la profondità del fondale oceanico supera 6.000 m, le onde di tsunami, non percettibili, possono viaggiare alla velocità di un jet commerciale, ovvero a circa 800 km l’ora. Possono spostarsi da un confine all’altro dell’Oceano Pacifico in meno di un giorno. E’ proprio questa loro estrema velocità che rende di fondamentale importanza l’individuazione di un maremoto nel momento in cui esso viene generato. I maremoti viaggiano a velocità molto minori in corrispondenza di bassi fondali marini, ma, contemporaneamente, l’altezza delle onde può aumentare in maniera drammatica.

Generation of Tsunamis

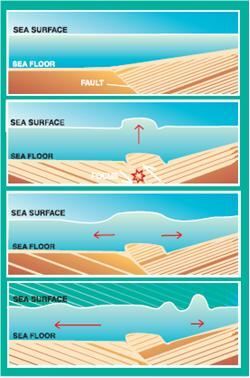

Once the event which initiates the tsunami occurs the potential energy that results from pushing water above mean sea level is then transferred to horizontal propagation of the tsunami wave (kinetic energy). The return of the sea level to its normal position generates a series of waves propagating in all directions from the initially deformed area.

Propagation of Tsunamis The speed at which the tsunami travels depends on the water depth. If the water depth decreases, tsunami speed decreases. In the mid-Pacific, where the water depths reach 4.5 kilometers, tsunami speeds can be more than 900 kilometers per hour. Refraction and diffraction of waves are important to the tsunami propagation.

Refraction Consider progressive waves with wavelengths much larger than the water depths over which they propagate. These are called shallowwater or long waves. Because the waves are long, different parts of the wave might be over widely varying depths (especially in coastal areas) at a given instant. As depth determines the velocity of long waves, different parts travel with different velocities, causing the waves to bend, and this is called wave refraction. (Shallower the water depth, less is the velocity.)

Diffraction Diffraction can be considered as the bending of waves around objects. It is this kind of movement that allows waves to move past barriers into harbors as energy moves laterally along the crest of the wave. Offshore and coastal features can therefore determine the size and impact of tsunami waves. Reefs, bays, entrances to rivers, undersea features and the slope of the beach all help to modify the tsunami as it attacks the coastline. When the tsunami reaches the coast and moves inland, the water level can rise many meters. In extreme cases, water level has risen to more than 15 m for tsunamis of distant origin and over 30 m for tsunami waves generated near the earthquake’s epicenter. Since the first wave may not be the largest in the series of waves, one coastal community may see no damaging wave activity while in another nearby community destructive waves can be large and violent. The flooding can extend inland by 300 m or more, covering large expanses of land with water and debris.

Non esiste un maremoto tipico, ognuno è differente. Tuttavia, i maremoti sono tutti caratterizzati da un elevato contenuto di energia, maggiore anche rispetto a quello delle più forti onde da vento.

Rispetto, invece, ai meccanismi che li generano, i maremoti possono essere classificati come indotti da terremoti, da vulcani, da frane e da impatti (ad esempio dovuti ad asteroidi).

In base, poi, alla distanza tra il punto in cui si generano e la costa su cui si abbattono, possono essere distinti in “maremoti lontani” e “maremoti locali”.

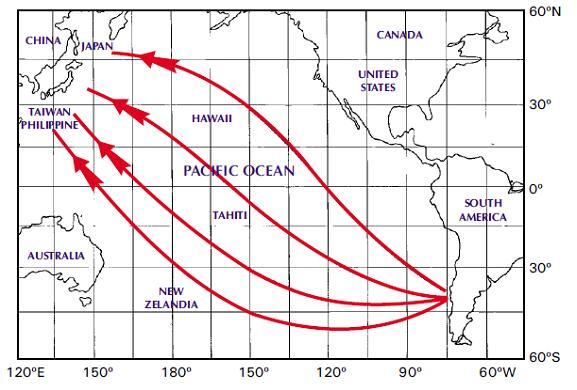

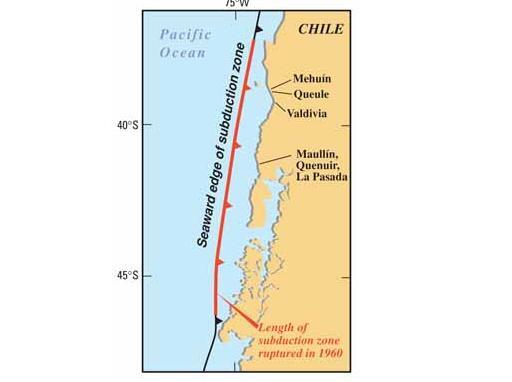

When a tsunami travels a long distance across the ocean, the sphericity of the Earth must be considered to determine the effects of the tsunami on a distant shoreline. Waves which diverge near their source will converge again at a point on the opposite side of the ocean. An example of this was the 1960 tsunami whose source was on the Chilean coastline, 39.5S., 74.5 W. The coast of japan lies between 30 and 45N. and about 135 to 140 E., a difference of 145 to 150 longitude from the source area. As a result of the convergence of unrefracted wave rays, the coast of japan suffered substantial damage and many deaths occurred.

As a tsunami approaches a coastline, the waves are modified by the various offshore and coastal features. Submerged ridges and reefs, the continental shelf, headlands, the shapes of bays, and the steepness of the beach slope may modify the wave height, cause wave resonance, reflect wave energy, and/or cause the waves to form bores which surge onto the shoreline.

Ocean ridges provide very little protection to a coastline. While some amount of the energy in a tsunami might reflect from the ridge, the major part of the energy will be transmitted across the ridge and onto the coastline. The 1960 tsunami which orignated along the coast of Chile is an example of this. That tsunami had large wave heights along the entire coast of Japan, including the islands of Shikoku and Kyushu which lie behind the South Honshu Ridge.

Locally generated Tsunamis

When a locally generated tsunami occurs, it impacts coastal areas a very short time after the event which produced the tsunami (earthquake, submarine volcanic eruption or landslide). Lapses as short as two minutes have been observed between the earthquake’s occurrence and the tsunami arrival to the closest shore. Because of this, a tsunami warning system is useless in this type of event and we should not expect instructions from an established system to react and keep us safe from the possible tsunami impact. This operation incapability of the warning systems is further increased by the communications and systems collapse generated by the earthquake. Hence, it is necessary to prepared in advance a proper response plan in case of a tsunami.

Gli impulsi che generano i maremoti possono avere origine da frane, vulcani o da impatti di oggetti provenienti dallo spazio (come meteoriti, asteroidi e comete), ma, in gran parte, da terremoti sottomarini.

Come si generano i maremoti

Dopo che si è verificato l’evento che ha generato il maremoto, l’energia potenziale risultante dalla spinta dell’acqua oltre il livello medio del mare si trasforma in energia cinetica, in grado di propagare orizzontalmente l’onda di maremoto. Il ritorno del livello del mare alla sua posizione iniziale genera una serie di onde che si propagano in tutte le direzioni, a partire dall’area di inziale deformazione (Figura 1).

Propagazione dei maremoti

La velocità di spostamento di un’onda di maremoto dipende dalla profondità del fondale marino. Se tale profondità diminuisce, la velocità del maremoto diminuisce. Nel Pacifico centrale, dove la profondità del fondale raggiunge 4,5 km, le velocità dei maremoti possono superare i 900 km all’ora. La rifrazione e la diffrazione delle onde sono elementi importanti nella propagazione dei maremoti.

MAREMOTI GENERATI DA TERREMOTI

I maremoti generati da terremoti si verificano quando il fondale marino si deforma in modo repentino, dislocando il volume d’acqua sovrastante dalla sua posizione d’equilibrio (Figura 1). In ogni caso, non tutti i terremoti generano maremoti. Per generare un maremoto occorre che la faglia sismogenetica sia al di sotto o prossima al fondale marino e provochi un movimento verticale del fondale stesso (fino a diversi metri) su di una vasta area (fino a 100.000 km quadrati). Terremoti poco profondi (generati a profondità inferiori a 70 km), che si verificano in corrispondenza di zone di subduzione (dove una placca oceanica scivola sotto ad una placca continentale o sotto una placca oceanica più giovane) generano i maremoti più distruttivi.

MAREMOTI GENERATI DA FRANE

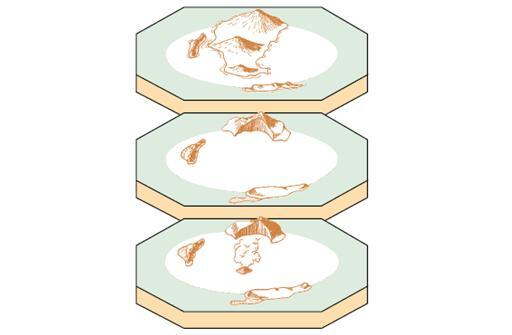

Le frane (sia sottomarine che sub-aeree), che spesso si attivano a seguito di un forte terremoto, possono a loro volta generare maremoti. In occasione dell’innesco di una frana sottomarina, il livello di equilibrio del mare viene modificato dal movimento dei sedimenti lungo il fondale marino.

MAREMOTI GENERATI DA VULCANI

Anche una violenta eruzione vulcanica in mare può generare una forza impulsiva capace di dislocare un determinato volume d’acqua e dare luogo ad un maremoto.

MAREMOTI GENERATI DA IMPATTI

Fortunatamente sono rari gli impatti di asteroidi o meteoriti sulla superficie della Terra. Non vi sono documenti storici che attestino maremoti causati dall’impatto di meteoriti o di asteroidi. In ogni caso, poiché sono noti, nel passato, impatti di meteoriti ed asteroidi sulla Terra, alcuni di essi possono aver impattato gli oceani ed i mari, dato che l’80% della superficie globale è ricoperta da acqua. La loro caduta in acqua potrebbe dare luogo a maremoti catastrofici.

One of the most destructive tsunamis in recent history was generated along Chile’s coast by an earthquake in May 22, 1960 (Figure 2). Every coastal town between latitudes 36S and 44S was destroyed or severely damaged by the action of the tsunami and the earthquake. In Chile, the double combination of earthquake and tsunami produced more than 2,000 deaths, 3,000 injured, two million homeless, and damage worth $550 million (US). The tsunami caused 61 deaths in Hawaii, 20 in the Philippines, 3 in Okinawa, and more than 100 in Japan. The height of the waves ranged from 13 meters at Pitcairn Islands, 12 meters at Hilo, Hawaii, and 7 meters at several places in Japan, to minor oscillations in other areas.

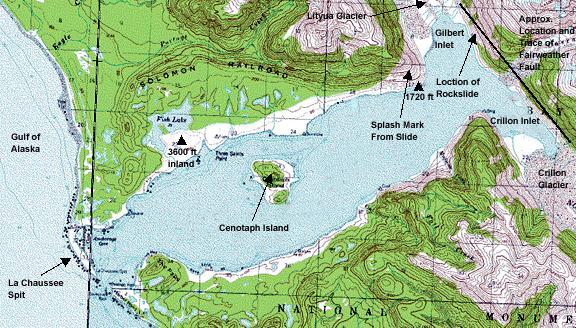

One of the most interesting landslide generated tsunamis happened in 1958 where about 81 million tones of ice and rock crashed into Lituya Bay, Alaska, Fifuren3). An earthquake had shaken the enormous mass loose. The landslide created a tsunami which sped across the bay. Waves splashed up to an astonishing height of 350 to 500 metres – the highest waves ever recorded. They scrubbed the mountain slope clean of all trees and shrubs. Miraculously, only two fishermen were killed.

In 1883, a series of volcanic eruptions at Krakatau in Indonesia created a powerful tsunami. As it rushed towards the islands of Java and Sumatra, it sank more than 5,000 boats and washed away many small islands. Waves as high as a 12-story buildings wiped out nearly 300 villages and killed more than 36,000 people. Scientist believe that the seismic waves traveled two or three times around the Earth.

In 1997, scientists discovered evidence of an asteroid with a four kilometre (2.5 mile) diameter that landed offshore of Chile approximately two million years ago, producing a huge tsunami that swept over portions of South America and Antarctica. Scientists have concluded that the impact of a moderately large asteroid, five to six kilometres (three to four miles) in diameter, falling between the Hawaiian islands and the west coast of North America would produce a tsunami that would attack cities on the west coasts of Canada, the United States and Mexico and would cover most of the inhabited coastal areas of the Hawaiian islands. (“Tsunami Teacher”, Educational material prepared by UNESCO-IOC www.unesco.org)

It has not happened, but conceivably, a tsunami could also be generated by very large nuclear explosions.

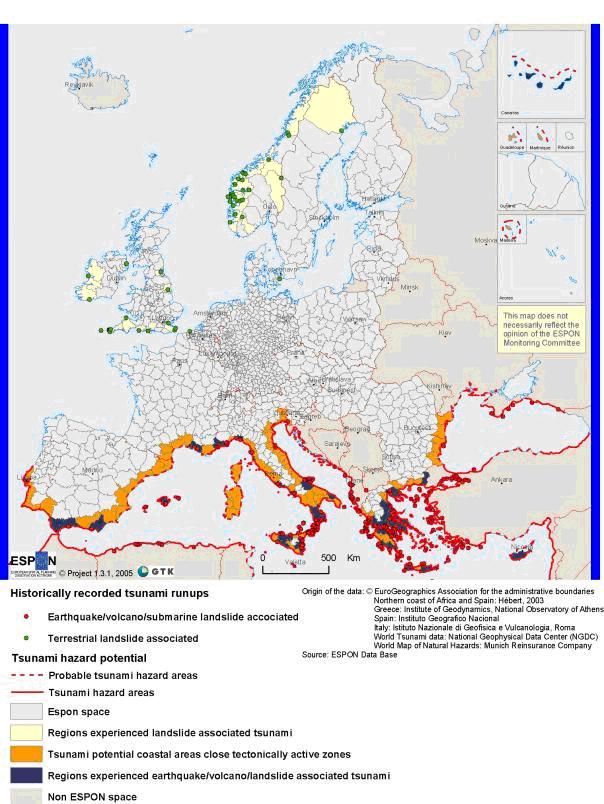

Il Pacifico è di gran lunga l’area ove si ha la frequenza maggiore di maremoti, secondo la National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration degli Stati Uniti d’America (NOAA, www.noaa.gov). Maremoti si sono verificati, in passato, anche nelle acque dei Caraibi, del Mediterraneo e degli Oceani Indiano ed Atlantico. Tra quelli che hanno interessato l’Atlantico Settentrionale vi è quello associato al terremoto di Lisbona del 1775, che provocò la morte di 60.000 persone in Portogallo, Spagna e Nord Africa. Quel terremoto generò un maremoto che raggiunse i Caraibi con onde di 7 m di altezza.

I Caraibi sono stati colpiti da 37 maremoti a partire dal 1498. Alcuni si generarono localmente; altri in zone remote, come nel caso del terremoto del Portogallo. La somma delle vittime di tutti questi maremoti si avvicina a 9.500.

Il Mediterraneo, il Mar Nero ed il Mar Rosso rappresentano la seconda più comune zona sorgente di maremoti dopo il Pacifico, con 98 maremoti osservati. I sistemi di allerta per quest’area sono approntati per far fronte a maremoti locali, che possono raggiungere le coste nel giro di pochi minuti. Probabilmente, il più famoso maremoto, sebbene non ben verificato, fu quello responsabile della scomparsa di Santorini, nel 1400 a.C., e che si stima abbia causato circa 100.000 vittime.

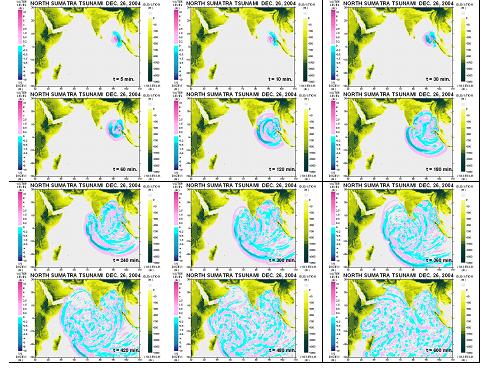

The devastating mega thrust earthquake (Indonesia/ Nicobar/ Andaman/ Sumatra Earthquake) of December 26, 2004, occurred on Sunday, December 26, 2004 at 00:58:53 GMT (7:58:53 AM local time at epicenter) with Mw=9.0 NEIC Epicenter Latitude 3.32 North, Longitude 95.85 East (USGS) or 3.09N, 94.26E southwest Banda Aceh in Northern Sumatra (Borrero, 2005). The earthquake has also triggered giant tsunami and the tsunami waves that propagated throughout the Indian Ocean and have caused extreme inundation and extensive damage, loss of property and life along the coasts of 12 surrounding counties in the Indian Ocean. The loss of lives has also been extended to the people from totally 27 countries from other parts of the world. (www.yalciner.metu.edu.tr/malaysia).

I danni prodotti da un maremoto sono in gran parte dovuti all’impatto delle onde, agli alluvionamenti, all’erosione delle linee di costa, delle fondazioni degli edifici, dei ponti e delle strade. Il grado di danneggiamento può essere amplificato dall’impatto dei detriti, delle barche e delle macchine trasportati dalle acque contro gli edifici. Forti correnti, spesso associate a maremoti, possono incrementare i danni strappando chiatte e barche dai loro ormeggi. Ulteriori danni sono determinati da incendi, che si sviluppano in corrispondenza di fuoriuscite di oli combustibili, e da contaminazioni di inquinanti, provenienti da rotture di fognature e da dispersioni di sostanze chimiche. Tutto questo produce perdite di vite umane e di risorse socio-economiche, ambientali e culturali.

| Country | Dead | Missing |

|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 125,598 | 94,574 |

| Thailand | 5,395 | 3,001 |

| Sri Lanka | 30,957 | 5,637 |

| India | 10,749 | 5,640 |

| Myanmar | 61 | – |

| Maldives | 82 | 26 |

| Malaysia | 68 | – |

| Somalia | 298 | – |

| Tanzania | 10 | – |

| Bangladesh | 2 | – |

| Kenya | 1 | – |

| TOTAL | 173,221 | 108,878 |

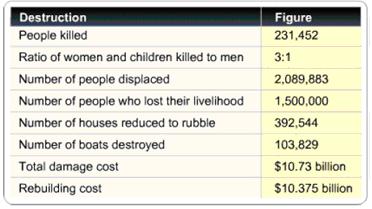

There are three factors of destructions from tsunamis: inundation, wave impact on structures, and erosion. Agricultural areas are fully flooded and destroyed beyond recovery for many years to come. Strong, tsunami-induced currents lead to the erosion of foundations and the collapse of bridges and seawalls, infrastructures. Flotation and drag forces move houses and overturn railroad cars. Considerable damage is caused by the resultant floating debris, including boats and cars that become dangerous projectiles that may crash into buildings, break power lines, and may start fires. Fires from damaged ships in ports or from ruptured coastal oil storage tanks and refinery facilities can cause damage greater than that inflicted directly by the tsunami. Of increasing concern is the potential effect of tsunami draw down, when receding waters uncover cooling water intakes of nuclear power plants. For 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami total destruction figures are presented below:

Tsunami impacts on the environment in many ways, from the death of marine life to the destruction of livestock, plant life and the impact on geological features as well as damage to mangroves, coral reefs and vegetation. Of great concern are damage to marine habitats and the impacts on coastal towns that are intertwined with fragile marine systems.

Tsunami-induced environmental problems include:

- Ground water contamination.

- Damage to coral reefs, sea grass beds and mangrove ecosystems. o Salinisation of soils and damage to vegetation and crops.

- Tsunami-generated waste and debris. o Impacts on sewage collection and treatment systems.

- Damage to protected areas. o Coastline erosion and inundation.

- Changes in river hydrology.

- Loss of livelihoods based on natural resources or ecosystem services.

Archaeological sites, historical ruins, naturally beautiful places are lost under the impact of tsunami forces and due to inundation.

Sì: mentre questi disastri naturali non possono essere evitati, i loro effetti (ovvero la perdita di vite umane e i danni alla proprietà) possono essere ridotti attraverso un’adeguata pianificazione territoriale.

Per fare questo, però, dobbiamo ben conoscere non solo la natura fisica del fenomeno e le sue dinamiche nelle varie aree geografiche, ma anche le combinazioni dei fattori fisici, sociali e culturali che caratterizzano ognuna di quelle stesse aree. Alcune di tali aree sono più vulnerabili ai maremoti di altre. Poiché i maremoti sono più frequenti nell’Oceano Pacifico, il maggior numero di esempi di gestione della pericolosità da maremoti si può trovare in tale area del mondo. Al di la di quanto remota possa essere la possibilità che si verifichi un maremoto, questa dovrebbe essere sempre considerata nella gestione delle aree costiere in sviluppo.

Anche se un certo grado di rischio può essere accettabile, le agenzie governative dovrebbero promuovere lo sviluppo e la crescita della popolazione in aree a maggior sicurezza ed a minore rischio potenziale. Tali agenzie dovrebbero regolamentare l’uso del suolo di una determinata area costiera avendo sempre presente il potenziale rischio maremoti, in particolare se l’area è stata già danneggiata da meremoti in passato. Deve essere evitata la distruzione della vegetazione naturale esistente che, come nel caso delle mangrovie, rappresenta una barriera naturale rispetto ai maremoti. La densificazione dell’edificato in zone a rischio può accrescere il rischio di danno.

I sistemi di allerta maremoti identificano terremoti potenzialmente pericolosi e forniscono un immediato allarme alle regioni che possono essere colpite dall’onda di maremoto. Il coordinamento dei sistemi di allerta globali è affidato all’Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC, http://www.ioc-tsunami.org) dell’UNESCO, col supporto del suo International Tsunami Information Centre. Sulla scorta della sua esperienza nel Pacifico, l’IOC sta attualmente realizzando sistemi di allerta maremoti nell’Oceano Indiano, nei Caraibi, nell’Atlantico e nel Mediterraneo.

No, poiché le cause di un maremoto sono rappresentate principalmente da processi naturali che, ad oggi, si verificano in modo imprevedibile, come terremoti, frane ed eruzioni vulcaniche. È possibile, comunque, che onde di maremoto possano essere generate anche da grandi esplosioni nucleari, sebbene ad oggi una tale situazione non si sia mai verificata.

Data la nostra attuale impossibilità a prevedere terremoti e frane (si vedano anche le sezioni dedicate ai terremoti ed alle frane) e la limitata capacità di prevedere eruzioni vulcaniche (si veda la sezione dedicata ai vulcani), è virtualmente impossibile prevedere, od oggi, i maremoti.

In ogni caso, considerando i maremoti del passato, gli scienziati conoscono le possibili zone di origine dei maremoti e le zone di potenziale impatto. Tali zone di potenziale impatto corrispondono ad aree geologicamente attive, caratterizzate da terremoti e da presenza di vulcani attivi. Non necessariamente, però, tutti i terremoti, le eruzioni vulcaniche o le frane possono generare maremoti. Il poter misurare l’altezza delle onde generate dai maremoti del passato può essere molto utile per prevedere l’impatto di maremoti futuri ed il limite di alluvionamento in specifiche zone comunità costiere.

Si può veramente fare poco per prevenire il verificarsi di pericolosità naturali (ed in particolare i maremoti). L’uomo, però, grazie alla sua estrema adattabilità, ha imparato a convivere con tutte le pericolosità.

Un fattore importantissimo nel ridurre le perdite dovute a questa pericolosità naturale è rappresentato da un’adeguata programmazione delle misure di protezione e di previsione. Misure di protezione correntemente in uso sono i sistemi di allerta per maremoti, dotati di strumentazione tecnologica avanzata per la raccolta di dati e per la comunicazione delle allerte. Paesi come il Giappone, la Russia, il Canada e gli Stati Uniti hanno sviluppato sistemi di allerta sofisticati ed hanno assunto la responsabilità di condividere, con altri paesi, le informazioni utili per predisporre l’allerta.

Nel 1965, l’Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission dell’UNESCO (UNESCO/IOC) ha accolto l’offerta degli Stati Uniti di ampliare il loro centro maremoti di Honolulu trasformandolo nel Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC, http://ptwc.weather.gov/). Vennero inoltre istituiti l’International Co-ordination Group (ICG/ITSU), successivamente chiamato Intergovernmental Coordination Group for the Pacific Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System (ICG/PTWS), e l’International Tsunami Information Center (ITIC, http://ptwc.weather.gov/), per supervisionare le attività dell’International Tsunami Warning System for the Pacific (ITWS). Questa impostazione ha facilitato collaborazioni a livello internazionale e tra molti membri della regione del Pacifico. Il ICG/PTWS organizza regolarmente incontri per valutare miglioramenti e attività offerti dai suoi servizi.

Con 46 stati membri (al maggio 2018) del Pacifico e mari attigui, l’area di responsabilità del Pacific Tsunami Warning System (PTWS) comprende l’Oceano Pacifico le regioni del Pacifico meridionale e tutti i mari marginali (Philippine Sea, East China Sea, Yellow Sea, Sea of Okhotsk, Bering Sea, South China Sea, Java Sea, Arafura Sea, Sulawesi Sea, Mindanao Sea, Sulu Sea, Celebes Sea, Bismarck Sea, Solomon Sea, Coral Sea, Tasman Sea).

Simili Tsunami Warning Systems esistono anche per l’Oceano Indiano (IOTWS), l’Oceano Atlantico Nord Orientale, il Mar Mediterraneo e mari connessi (ICG/NEAMTWS).

One of the cornerstones of tsunami mitigation is hazard assessment: through this process, vulnerable coastal areas are mapped and the potential risk for people living there is identified.

The value of information was dramatically illustrated during the Indian Ocean tsunami. Most victims received no warning – but thousands of lives were saved in cases where tsunami knowledge existed and was used.

Experts have argued that tsunami warning systems need to be underpinned by public awareness campaigns and emergency response plans if they are to be effective.

Warnings are of little use if people do not know how to respond to them. Knowledge becomes even more critical if warning times are short – or there is no warning at all – in which case people must know how to react immediately.

The value of indigenous knowledge was highlighted by Simuelue islanders (Indonesia), who lost only seven of their 78,000 inhabitants even though the 2004 tsunami struck them just eight minutes after the earthquake. They have kept alive, through oral history, the lessons of a tsunami that struck in 1907 (known as “smong”): Simuelue islanders knew exactly what to do when the tsunami happened while populations of other nearby coastal areas were decimated.

A tsunami mitigation plan needs to:

- Quickly confirm potentially destructive tsunamis and reduce false alarms.

- Address local tsunami mitigation and the needs of coastal residents.

- Improve coordination and exchange of information to better utilize existing resources.

- Sustain support at state and local level for long-term tsunami hazard.

- Improve the awareness and preparedness of communities for tsunamis:

- Raise the awareness of affected populations.

- Supply tsunami evacuation maps.

- Improve tsunami warning systems.

- Incorporate tsunami planning into state and federal all-hazards mitigation programmes.

Civil defence authorities in each country can initiate public education programme consisting of seminars and workshops for responsible government officials, can publish informational booklets on the hazards of tsunami, and can co-ordinate with the communications media on the announcement of tsunami information. Other government agencies can take action also to mitigate future losses from tsunami. For example, government agencies can develop sound coastal management policies, which include zoning and planning for tsunami-prone coastal areas.

Internally, government agencies can streamline and co-ordinate their operating procedures and communications so they can perform efficiently when the tsunami threat arises. Procedures related to tsunami warnings should be reviewed frequently to define and determine better respective responsibilities between the different government agencies at all levels.

Scientific organizations can undertake research and engineering studies in developing evacuation zones or engineering guidelines for building coastal structures. Audio-visual materials can be prepared for educating children in schools and the public in general. Brochures and pamphlets can be printed describing the tsunami warning system and what the public can do in time of tsunami warning.

The natural environment can provide protection against tsunamis, and environmental destruction to make way for development can raise the tsunami risk of coastal communities. Tropical coastal ecosystems have sophisticated natural insurance mechanisms to help them survive the storm waves of typhoons and tsunamis such as coral reefs being equivalent of natural breakwaters causing waves to break offshore and allowing them to dissipate most of their destructive energy before reaching the shore.

Mangrove forests also act as natural shock absorbers, “soaking up destructive wave energy and buffering against erosion”. Systems of marshes, tidal inlets and mangrove channels also help limit the extent of inundation by floodwaters and enable flood waters to drain quickly.

Places that had healthy coral reefs and intact mangroves were far less badly hit than places where the reefs had been damaged and the mangroves ripped out and replaced by beachfront hotels and prawn farms during 2004 Tsunami.

However, there has been widespread destruction of natural coastal habitats to make way for urban development, population growth, industry, aquaculture, agriculture and tourism.

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF, http://www.worldwildlife.org) has recommended that tsunami mitigation strategies take into account:

- Rehabilitation and restoration of degraded coastal ecosystems that help protect from storm waves, especially coastal marshes and forests, mangroves and coral reefs.

- Adoption of integrated coastal zone management, including zoning and mandatory coastal setback. For example, hotels should not be built within a safety zone from the high tide mark.

- Strict enforcement of land and coastal-use planning and policies, including natural disaster risk assessments.

- Implementation of incentives to ensure that sensitive facilities are built away from high risk areas.

- Risk assessment that helps reduce the vulnerability of coastal development.

Si può conseguire un’accresciuta consapevolezza della potenziale minaccia maremoti attraverso un programma educativo pubblico costituito da seminari e workshp per il personale ufficiale addetto e attraverso depliant informativi sul pericolo maremoti e su cosa si debba fare in caso di maremoti.

- A strong earthquake felt in a low-lying coastal area is a natural warning of possible, immediate danger. Keep calm and quickly move to higher ground away from the coast.

- Tsunamis can occur at any time, day or night. They can travel up rivers and streams that lead to the ocean.

- A tsunami is not a single wave, but a series of waves. Stay out of danger until an “ALL CLEAR” is issued by a competent authority.

- Approaching tsunamis are sometimes heralded by noticeable rise or fall of coastal waters. This is nature’s tsunami warning and should be heeded.

- A small tsunami at one beach can be a giant a few miles away. Do not let modest size of one make you lose respect for all.

- Sooner or later, tsunamis visit every coastline around the ocean.

- All tsunamis, like hurricanes, are potentially dangerous even though they may not damage every coastline they strike. • Never go down to the beach to watch for a tsunami! • WHEN YOU CAN SEE THE WAVE YOU ARE TOO CLOSE TO ESCAPE.

- Tsunamis can move faster than a person can run!

- During a tsunami emergency, your local emergency management office, police, fire and other emergency organizations will try to save your life. Give them your fullest cooperation.

- Homes and other buildings located in low lying coastal areas are not safe. Do NOT stay in such buildings if there is a tsunami warning.

- The upper floors of high, multi-story, reinforced concrete hotels can provide refuge if there is no time to quickly move inland or to higher ground.

- Stay tuned to your local radio, marine radio, NOAA Weather Radio, or television stations during a tsunami emergency – bulletins issued through your local emergency management office and National Weather Service offices can save your life.

- Since tsunami wave activity is imperceptible in the open ocean, do not return to port if you are at sea and a tsunami warning has been issued for your area. Tsunamis can cause rapid changes in water level and unpredictable dangerous currents in harbours and ports.

- If there is time to move your boat or ship from port to deep water (after a tsunami warning has been issued), you should weigh the following considerations:

- Most large harbors and ports are under the control of a harbor authority and/or a vessel traffic system. Keep in contact with the authorities should a forced movement of vessel be directed.

- Smaller ports may not be under the control of a harbor authority. If you are aware there is a tsunami warning and you have time to move your vessel to deep water, then you may want to do so in an orderly manner, in consideration of other vessels.

- Damaging wave activity and unpredictable currents can affect harbors for a period of time following the initial tsunami impact on the coast. Contact the harbor authority before returning to port making sure to verify that conditions in the harbor are safe for navigation and berthing.

Mentre una comunità costiera può non subire alcun danno dalle onde di maremoto, una comunità vicina può invece essere gravemente colpita e devastata.

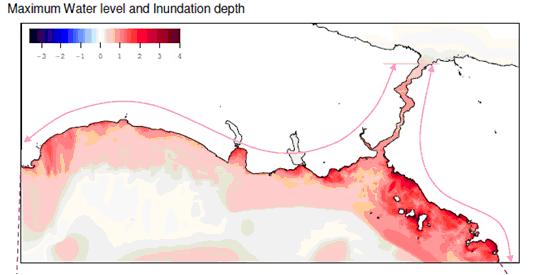

I modelli numerici sviluppati per prevedere il potenziale di inondazione da maremoto – la penetrazione nell’entroterra delle onde a partire dalla costa – possono identificare le aree che con maggior probabilità verranno inondate in occasione di maremoto (favorendo la costruzione di carte di pericolosità/vulnerabilità), nonché quali percorsi possono essere utilizzati dalle persone per raggiungere agevolmente zone sicure (favorendo la costruzione di carte di evacuazione).

Le carte delle zone inondabili da maremoto – aree potenzialmente raggiungibili dalle grandi onde – possono essere utilizzate dai pianificatori e dai politici per istituire zone d’evacuazione e percorsi per raggiungere zone sicure.

A questo scopo, le osservazioni del limite raggiunto dalle acque e delle zone inondate in occasione di maremoti precedenti divengono essenziali per verificare la validità delle mappe prodotte attraverso l’utilizzo dei modelli numerici.

One of the key tools for tsunami mitigation is the study and production of hazard maps of local coastal areas to ascertain how vulnerable they are to tsunamis – this can vary greatly along shorelines depending on the intensity of the waves, undersea features and the topographical lay of the land.

Hazard maps require knowledge of the historical tsunami record in order to estimate the probability that a tsunami will occur in the future. An integral part of emergency preparedness is understanding the tsunami hazard or threat. Since earthquakes are the most probable source, seismic hazard maps are needed to identify the potential earthquake source zones. In the case of tsunamis, this also includes trying to predict the potential height of waves.

In high-risk areas where the maximum potential source of a tsunami is known – for example if there is an active earthquake subduction zone offshore – tsunami generation, propagation and run-up can be mathematically modelled and wave heights estimated. Also, historical records of previous tsunamis charting earthquake magnitudes, and wave heights and run-up and inundation patterns, can be used to support tsunami hazard predictions.

One such study as outlined previously was performed for Istanbul, Turkey (Figure 1). Comprehensive tsunami simulations were based on 49 different scenarios considering not only active faults but also submarine landslide induced tsunamis by using OIC, a widely accepted, scientifically verified tsunami simulation code TUNAMI N2. The animations of the selected scenarios have been prepared by METU, The Department of Civil Engineering, Ocean Engineering Research Center using the tsunami simulation and visualization code NAMI DANCE, which has been developed for tsunami numerical modeling and simulations by Profs..Nobuo Shuto and Fumihiko Imamura in Tohoku University Japan. TUNAMI N2 determines the tsunami source characteristics from earthquake rupture characteristics. It computes all necessary parameters of tsunami behavior in shallow water and in the inundation zone allowing for a better understanding of the effect of tsunamis according to bathymetric and topographical conditions. For further information, http://yalciner.ce.metu.edu.tr/marmara/index_eng.htm

Tectonically induced tsunamis occur in Europe mainly in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. There are several geological and historical records of tsunamis (see above). The most endangered zones lie in close vicinity to the main volcanoes or along seismically active zones. Tsunamis caused by (submarine) landslides have mainly occurred in Norway, but also in some other areas in Europe (Figure 1). Often it is difficult to distinguish if an earthquake caused a tsunami or if an earthquake triggered a (submarine) landslide that then caused a tsunami. In general it can be concluded that tsunamis are possible along all shorelines that lie in tectonically active zones and/or in areas where (submarine) landslides are possible. Even though no devastating tsunamis have occurred in Europe in the last 100 years, the potential hazard is still high. (http://www.gsf.fi/projects/espon/Tsunamis.htm)