La sécheresse est un état (normal ou momentané) du sol et/ou une situation dans laquelle la région doit faire face à une déficience dans son approvisionnement ordinaire en eau, sur une période suffisamment prolongée pour qu’on observe des impacts sur la flore naturelle ou cultivée (Wikipédia).

Dans un sens large, la désertification peut être le synonyme d’une crise environnementale qui peut être à l’origine de conditions ou de paysages similaires à ceux d’un désert (Encyclopaedia of Environ. Sciences, 1999).

La sécheresse et la désertification ont des effets sur tous les aspects de la vie, ce qui montre bien à quel point l’environnement et les moyens de subsistance sont interdépendants.

Les risques afférents à la sécheresse et à la désertification sont les suivants :

Les risques pour l’environnement

La sécheresse et la désertification font parfois peser des risques irréversibles sur la biodiversité en termes d’appauvrissement de la biodiversité, des sols et de la végétation. Ils entraînent une modification de la composition floristique, une réduction de la biomasse qui recouvre le sol et une diminution des capacités de croissance et de reproduction de la végétation.

Les conséquences les plus inquiétantes en matière de biodiversité concernent :

- les animaux sauvages et domestiques, dont les conditions de gestion se détériorent ;

- la flore, dont certaines espèces sont menacées ;

- certains cours d’eau, dont le débit autrefois constant devient intermittent, qui perturbent le biotope de beaucoup d’espèces ;

- des oiseaux migrateurs qui font partie du patrimoine mondial occupent des habitats de plus en plus précaires du Sahel, dans les zones humides résiduelles.

Les risques en termes d’appauvrissement des sols, pour la végétation et la forêt

- Une dégradation liée à une surexploitation des sols jusqu’à l’épuisement, la surexploitation et la mauvaise utilisation des sols dans les régions arides, dues au changement climatique au niveau mondial ;

- une dégradation liée au surpâturage, qui détruit la couverture végétale qui protège les sols de l’érosion ;

- un appauvrissement des sols découlant de pratiques préjudiciables en matière d’irrigation, et impliquant une augmentation de la salinité et un assèchement des cours d’eau qui alimentent les grands lacs ;

- une déforestation qui élimine les arbres qui protègent le sol de l’érosion hydrique et éolienne. De plus, dans de nombreuses régions arides, le bois est la seule source indépendante d’énergie (éclairage, cuisine).

Dans des conditions de sécheresse extrême, les invasions de sauterelles ont des conséquences catastrophiques sur l’environnement et l’économie des pays fragiles.

Les risques pour l’économie

La sécheresse et la désertification ont des conséquences directes sur la diminution et les pertes de récoltes et, du fait de l’augmentation des prix des produits agricoles qui en découle, les populations (notamment rurales) ont des difficultés à satisfaire leur demande d’eau potable et de denrées pour nourrir leurs familles et leurs troupeaux.

Des études ont montré que les récoltes de riz chutent de 10 % dès que la température nocturne augmente d’un degré Celsius. Or, la diminution des récoltes de riz a de graves conséquences dans les pays producteurs.

Les risques en termes de pauvreté et de migrations massives

L’appauvrissement des sols est synonyme de famine et de pauvreté. Pour trouver d’autres moyens de subsistance, les populations qui vivent dans des zones menacées par la désertification sont contraintes de se déplacer. Généralement, elles émigrent vers les zones urbaines pour y bénéficier de meilleures conditions de subsistance, ou quittent leur pays. Les mouvements de population sont l’une des principales conséquences de la désertification. http://remi.revues.org/document1654.html.

Entre 1997 et 2020, quelque 60 millions de personnes auront quitté les zones désertiques subsahariennes de l’Afrique pour gagner le Maghreb et l’Europe, selon la Convention des Nations Unies sur la lutte contre la désertification.

Les risques pour la santé

La sécheresse et la désertification (qui sont des conséquences du changement climatique) perturbent les écosystèmes et favorisent la propagation de certains insectes et maladies qui présentent un danger pour les humains, les plantes et les animaux. Selon les résultats d’études menées, des températures moyennes plus élevées sont susceptibles d’accroître les taux de fertilité et de croissance des insectes ravageurs ainsi que la fréquence des épidémies, et de permettre par ailleurs aux insectes et aux maladies de se propager sur d’autres espaces géographiques.

- La santé des êtres humains

La sécheresse et la désertification (qui sont des conséquences du changement climatique) s’accompagnent généralement d’une dégradation qualitative et quantitative des ressources en eau et, bien souvent, du développement des épidémies (choléra, malaria, etc.).

Les vents, quand ils soulèvent des tempêtes de sable, sont aussi les vecteurs d’atteintes ophtalmologiques (conjonctivite) et de problèmes respiratoires.

Par ailleurs, alors que les mouvements migratoires dépeuplent les zones rurales, les villes se trouvent confrontées à des situations sanitaires désastreuses du fait du manque d’infrastructures pour le traitement des eaux usées et des effluents et pour la gestion des déchets. Dans ces conditions, les services médicaux et de prévention s’avèrent largement insuffisants.

- La santé des animaux et des végétaux

La sécheresse et la désertification (qui sont des conséquences du changement climatique) déciment les troupeaux privés de pâture. Par exemple, dans les pays du Sahel (durant les chaudes journées d’été), il arrive que les vaches meurent lorsqu’elles mettent bas et, souvent, les veaux sont prématurés. Les chirurgiens vétérinaires de ces régions expliquent l’apparition de nouvelles maladies par les changements climatiques.

La modification du régime des vents est susceptible de changer la répartition des insectes, mais aussi des bactéries et des champignons qui sont des vecteurs de maladies pour les plantes. La hausse des températures hivernales favorise la multiplication des pyrales qui perforent les tiges du riz, par exemple. Des études révèlent que le nombre de parasites et d’insectes, comme les guêpes et les mouches, qui pondent leurs œufs sur/à l’intérieur des chenilles diminue en cas de pluies irrégulières. Or, ces parasites sont très utiles dans la lutte biologique contre les ravageurs de beaucoup de cultures tropicales.

L’Organisation mondiale de la santé a établi un lien clair entre les fortes pluies qui ont affecté la majeure partie de l’Afrique de l’Est au début 2008 et la recrudescence de la malaria. La dengue par exemple, une maladie grave provoquée par un virus transmis par les moustiques, a atteint des niveaux de contagion catastrophiques dans les Caraïbes.

On observe l’apparition du mildiou dans certaines régions où l’on cultive la pomme de terre, une maladie qui tend à se répandre dans des conditions humides plus chaudes.

Les risques pour la sécurité alimentaire

La sécheresse et la désertification (qui sont des conséquences du changement climatique) sont indubitablement des menaces pour la sécurité alimentaire des 9 milliards d’individus que la terre devra nourrir au milieu du 21e siècle. Il faudrait pour cela tripler la capacité de production alimentaire d’ici 2050. Néanmoins, paradoxalement, les surfaces arables diminuent. Il est prévu que les pays développés verront leurs surfaces arables passer de 0,65 à 0,4 ha par personne entre 1990 et 2010.

Les risques liés au changement climatique (puits de carbone)

La sécheresse et la désertification conduisent à un appauvrissement du sol. Par conséquent, elles réduisent l’aptitude du sol à faire office de « puit de carbone » et, inversement, augmentent sa capacité à être une « source de carbone ».

Le sol et les écosystèmes terrestres jouent un rôle fondamental en tant que puits de carbone : ils collectent et stockent le carbone. Il a ainsi été estimé que les sols retiennent 2,3 Gt (gigatonnes) de carbone par an, ce qui représente plus d’un tiers du carbone émis par la combustion des combustibles fossiles qui sont à l’origine du changement climatique. Le stock total de carbone contenu dans les écosystèmes terrestres avoisine les 2 500 Gt, dont 2 000 Gt se trouvent dans le sol.

The drought is a major natural risk linked to long-term climatic abnormalities.

It appears by a drying out of the soil in other words a decline of its hydric potential resulting from an important pluviometric deficit (Lefèvre and Schneider, 2003).

If desert regions are subjected to quasi-permanent drought because of the presence of the subtropical high pressures. The zone of Sahel (Mauritania, Senegal, Niger, Chad and Côte d’Ivoire), undergo a rarefaction of rains more and more marked since 1968 to this day.

Certainly, the successive years of drought are interrupted by a return to normal (year 1 to 2) from time to time but the hydric deficit persists with peaks (73/77/82…).

Indeed, the measures made in the experimental fields of Senegal and Mauritania indicate that since 1968, isohyets 300/400 mm are uncalled-for from 100 to 200 km southward in the space of 15 years (from75 to 90) and no year was superfluous (Sircoulon, on 1992).

In the sector of the pluvial farming in Senegal, we record a clear production decrease of groundnut due to the useful shortening of the duration of rainy season and to the more and more frequent appearance of arid periods during the culture.

Although, in Sahel, the drought is at the origin of famine, of conflicts, of exodus and mortality (200 000 died only for the year 1973 when the drought reached its peak.)

The Mediterranean countries also know droughts of several months on the south bank (4 months in Tunis and Algiers, 7 months in Alexandria) and in a lesser degree the North shore (2 months in Barcelona and 3 months in Istanbul) with the exception of the South of Spain (Drain, 2006) already confronted with the water shortage (Margat, 1990).

Multiannual aridity also occurs in Mediterranean region. Besides, the fall of the agricultural productions (especially cereal), the droughts of the period 1990-1999 are also at the origin of the decay of the cedar of the ATLAS in Algeria and in Morocco. (Halitim, 2006).

In Europe, also the decay of the forest domains is also relatively important following the successive episodes of droughts between 1947 and 1976. In France, the drought from 1989 till 1992 engendered an drying out of streams (11000km), a reduction of the agricultural productions (especially those of May) and an increase of the frequency of the fires of bit in Southern zone especially (Lefèvre and Schneider, 2003).

According to the same authors, the aridity can lead disorders at the level of the constructions further to dehydrations of underground clays.

Nevertheless, the difference of rainfall between the North and the South of Sahara is very strong, because in Mediterranean region except the summer aridity, we find the rest of the year of more or less important rains (350 in 750m). Despite very different pluviometric regime, we can hold some criteria common to these arid climates:

- The global incapacity of the precipitation in view of the potential evaporation.

- A marked interannual irregularity

- The momentary excesses of water even in Sahelian region (SIRCOULON, 1992)

What constitutes a major constraint for the biological rise and a threat for the agriculture whose the socioeconomic impact is roughly more striking in the regions of the world where the followed of the populations is strictly connected to a food-producing agriculture and\or to a practice of the breeding as in Sahel.

The drought is also a factor of degradation of natural resources such as the vegetation, pastoral courses and soils, thus, accentuating the process of desertification. in fact, both of the drought and the desertification are very dependant phenomena. Therefore, the Convention to Combating Desertification encouraged countries of the world to begin to fight at the same time the desertification and the effects of the drought (OSS).

From the ecological point of view, desertification is defined as being the conjunction of two phenomena: the occurrence of the prolonged droughts and the excessive pressure of the man and his animals on unstable fragile ecosystems or little cancelling. (Le HOUEROU, 1979/1987).

In the broad sense, desertification can mean environmental crisis which produces conditions or nearby landscapes of those of a desert (Encyclopedia of Environ-Sciences, 1999).

We appoint by desertification, the ecological consequences of an aridification of the climate (Ramade, 2002).

In the sense of the United Nations convention, desertification is the degradation of land in arid and arid sub-humid areas. It occurs when soils are fragile, the vegetable cover is reduced and the particularly harsh climate ( 07-06-94 ).

There are more than 130 definitions of the word desertification in the literature according to Mainguet 1998.

The desertification knew numerous definitions which were the object of intellectual controversies. Beyond the political compromises, a consensual definition of the process was proposed by the Convention on the fight against the

Desertification: » the desertification is the degradation of land in arid and arid sub-humid areas due to various factors: including climatic variations and human activities « . The desertification thus concerns a process of degradation of lands linked to natural factors aggravated by the action of the man.

Indeed in arid regions, when the degradation of grounds accelerates ceaselessly, reducing the reserves of the productive grounds, it creates an environment similar to that of the deserts: we speak then about desertification. The desertification does not content with destroying the base of the productive resources, it also provokes the loss of the genetic resources, and it increases the atmospheric dust, disrupts the process of natural recycling of waters and disrupts the economy of a country pulling movements of populations. It is synonymic of loss of biological and economic productivity of arable, pastures and woody lands.

In view of the various examined definitions, the climate countered as a determining factor.

What is the climate determining?

The process of desertification appears, generally in the bioclimatic floors characterized by a pluviometer from 100 to 400 mm / year.

Besides, the irregularity and the level of precipitations, the strong temperatures, the drying winds loaded with particles of sand and the intensity of the ETP are so many factors deteriorating especially when the human activities are transplanted there.

The figure 3 illustrates the action combined by the natural and anthropological factors involved in the process of desertification.

The climate has diverse, direct and indirect incidences on ecosystems:

On water resources (weakness of the rainfall, the irregularity);

- Frequency and continuation of arid period;

- Aridity of streams and brooks;

On the type of vegetation, its distribution and its density

On grounds by reducing their rate of organic matter and their power of keeping back to water with increase of the risk of Salinization

In other words, by acting on these essential parameters, the climate shapes the ecosystems.

The anthropological action is also important. It falls on behind the step in the climatic action by amplifying the process.

How is the process of desertification made?

The desertification is distinguished from risks with shock effect (devastating floods, earthquakes, forest fires) by the involved mechanisms, by the mode of expression and by its spatiotemporal evolution.

Two factors seem essential so that the desertification occurs:

- Conditions of natural physical weakness (physical and biological);

- A strong human pressure exceeding the acceptable threshold.

As the vegetation declines grounds are subjected more and more to the degradation hazards (erosion, Salinization,) being able to lay bare the source rock.

When the vegetation disappears, the desertification accelerates leaving cleaned grounds where the hydrous and wind erosion causes important damages.

If this phenomenon occurred in an insidious and slow way even in the geologic scale, nowadays, the conjugation of several factors (natural and anthropological) seems to look to it a speed of perceptible acceleration and a faster extension.

For illustration:

In Sudan, the desert encroachment is from 90 to 100 km between 1956 and 1975;

In the Chad, the plant cover setting degraded of 32 % between 1954 and 1974;

In Tunisia, on a sample of 20 000 ha, 7500 ha are become depopulated or 347 % between 1965 and 1974. (The HOUEROU, 1979)

In Algeria, on a sample of 13 000ha, 500 000ha of the steppe become totally depopulated or 41 % (KARA 2000) with an effect more marked at the level of the steppe West where we also note a considerable regression of let us tax climatic (white Artemisia and Alfa), during these last years (SALAMANI and HIRCHE, 2007; AYDOND, on 2009)

In Spain, 31 % of lands would be threatened with desertification. The degradation of the socioeconomic conditions is in the heart of the problems of desertification:

destruction of the bases of production, social system in danger, impoverishment of the populations …

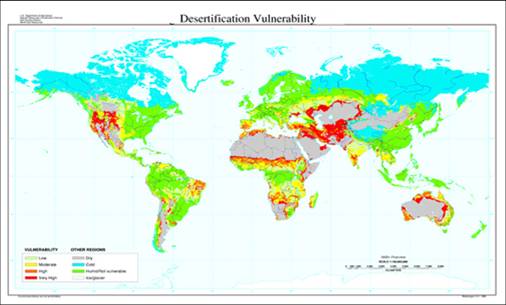

The scale of drought and desertification differs according to the zones of impact in the world: the phenomenon affects more than a country and more than a continent and tends to increase these last decades. Meadows of the third party of the appeared lands is threatened.

So, the vulnerable zones represented in figure 4 are situated in arid zones and semi arid in particular in the suburb of the climatic deserts.

The process seems to reach continents of which we thought formerly under cover such as Europe in particular in its south bank: the current situation of the South of Spain is worrisome (Figure 6).

The scale of desertification at the world level:

Meadows the third party (1/3) of the appeared lands is threatened

1 billion persons are concerned

A reduction of the farmlands of: 2/3 for Africa, 1/3 for Asia and 1/5 for the Latin America and the Caribbean (Caribbean islands) [Source: the UNO, the FAO and the UNESCO]

24 billion tons of fertile soils disappear every year.